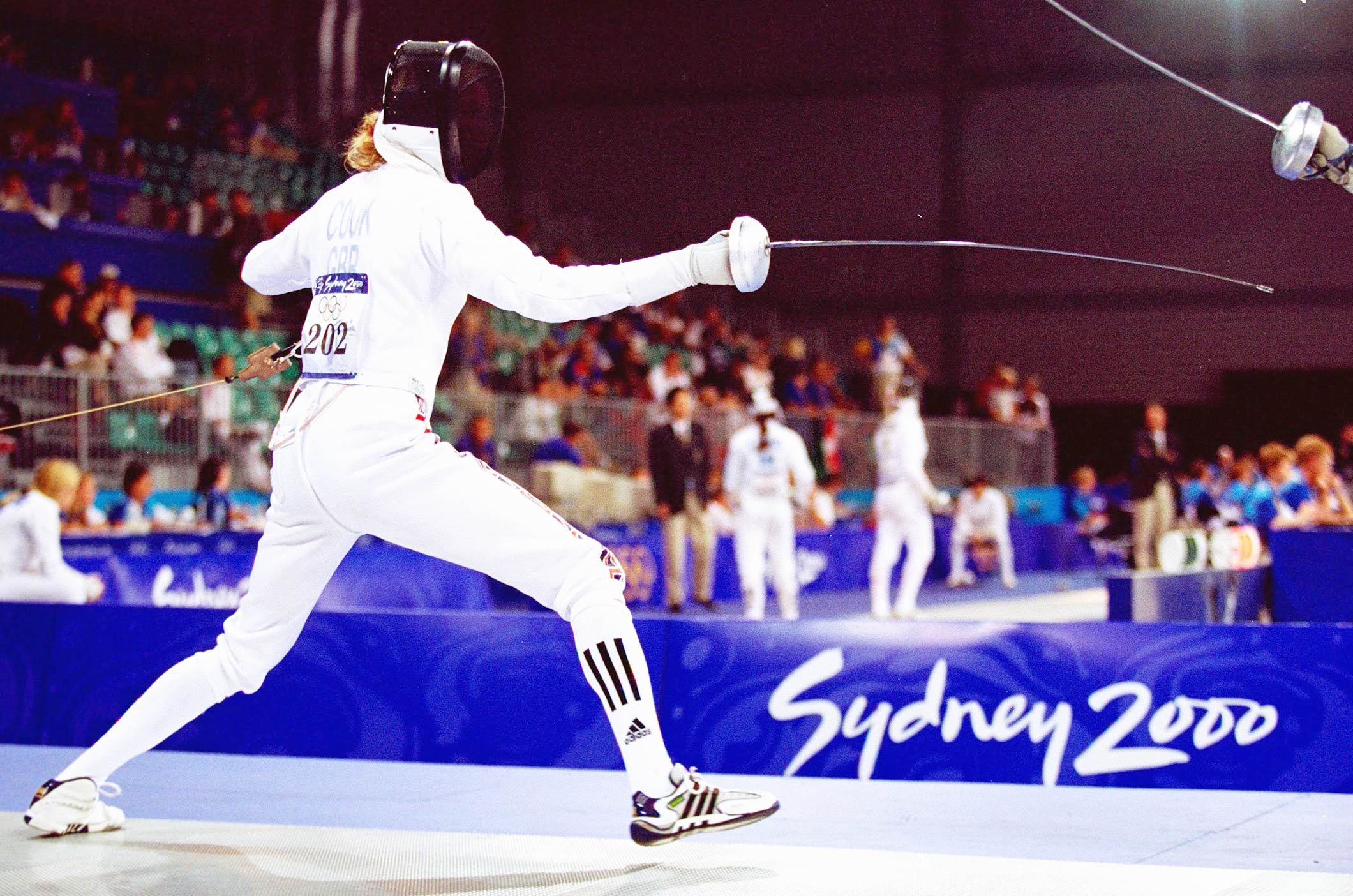

How Cook navigated route to historic gold in Australia combining medicine and modern pentathlon

While male pentathletes have competed at every Olympic Games since Stockholm 1912, Steph Cook became the first women’s Olympic modern pentathlon champion 88 years later, at the Sydney 2000 Games. The Great Britain star talks us through how she combined a hectic life as a doctor with going for gold – and how her fascinating sport, rooted in Olympic history, has evolved in the modern world.

Junior doctors in British hospitals are famously, perhaps notoriously, overworked. So the idea of pulling 15-hour shifts while also putting in the amount of training required to become an Olympian might seem physically impossible. Steph Cook, however, somehow managed it, and in a sport consisting of five disciplines – fencing, swimming, show jumping, shooting and running.

“It was crazy,” Cook said with a laugh, reflecting on her years before becoming the first women’s Olympic modern pentathlon champion. “I was studying medicine at Oxford, which is where I’d taken up modern pentathlon, and once I graduated I knew I needed to make a decision.

“Was I going to continue with sport or become a junior doctor? I decided I’d try to do both. I was doing up to 100 hours a week in the hospital while still training and competing. I remember coming off a night shift and flying straight to Poland for a World Cup. Somehow I kept going.”

Combining saving lives with creeping up the world rankings, Cook was clearly a multi-tasker of the highest calibre. No wonder the Olympic sport conceived to find the best all-round athletes appealed to her.

“Growing up, I’d done a bit of riding and was a good runner, and at university I thought I’d give pentathlon a go,” she said. “I really just wanted to get back on a horse again, but I also fancied the idea of trying some new sports. I had never shot or fenced before, and my swimming was ropey. I couldn’t even do tumble turns.

“Initially it was just fun. In 1994, when I started, the women’s sport wasn’t even at the Olympics. But I watched the men with interest at Atlanta 1996, and there was a campaign to get the women’s sport included.

“I got selected for the 1997 European Championships, but it clashed with my final medical exams and I couldn’t go. When the UK lottery funding came in, and the Olympics started to look more likely, I was offered a research position by a doctor in Oxford. It meant I could still study but also fit in more training. And then we got the National Training Centre in Bath. From November 1999, I trained full time.”

Having been in the sport for only six years, Steph was still under the radar in terms of becoming a potential medallist. But the unique nature of her sport gave her a chance. “Riding and running were my strengths, but they reckon it takes 10 years to get to international level in fencing,” she said. “I struggled with the complexity of it, but I just kept pushing. It’s about maximising every improvement.”

Intense work in the year before the Olympic Games Sydney 2000 paid off. Mornings would start with shooting, then a swim, and then there would be rides, fencing, runs and strength sessions. “They were full-on days, and it’s a fine balance between fitness and skills work,” Cook said. “But the training is fun. You can’t get bored, and it’s always a challenge.

“It’s also great being in a squad with different specialisms – you can pull each other up. We trained with internationals in each sport, too, which improves you.”

Sport guide: Modern Pentathlon Explained

By the time Sydney rolled around, Cook was ranked joint world No.1. “We were very lucky going to Sydney because we stayed up on the Gold Coast,” she said. “We flew down for the Opening Ceremony and felt the hype, the buzz, the atmosphere. The hairs stand up on the back of my neck thinking about it. But then we went back to Brisbane to concentrate on our sport.

“The British athletes would fly to Sydney and come back with their medals. There was a positive vibe in the camp, and it made you start to believe you could do it, too. We were competing on the final day and I had breakfast with the boxer Audley Harrison. By the evening, we both had gold medals.”

Modern pentathlon is a sport of many variables. A clipped fence, a wayward shot, a bad duel, a tired sprint finish: they can all be the difference between ecstasy and heartache. And while Cook did not have her best day ever, she held her nerve over the rest of the field.

“I’d been consistent all year and, while you always need a little bit of luck, everything came together – the work I’d put in with the coaches and psychologist,” she said. “There were maybe six to eight of us who could have won, but it’s about staying in control of what you can.

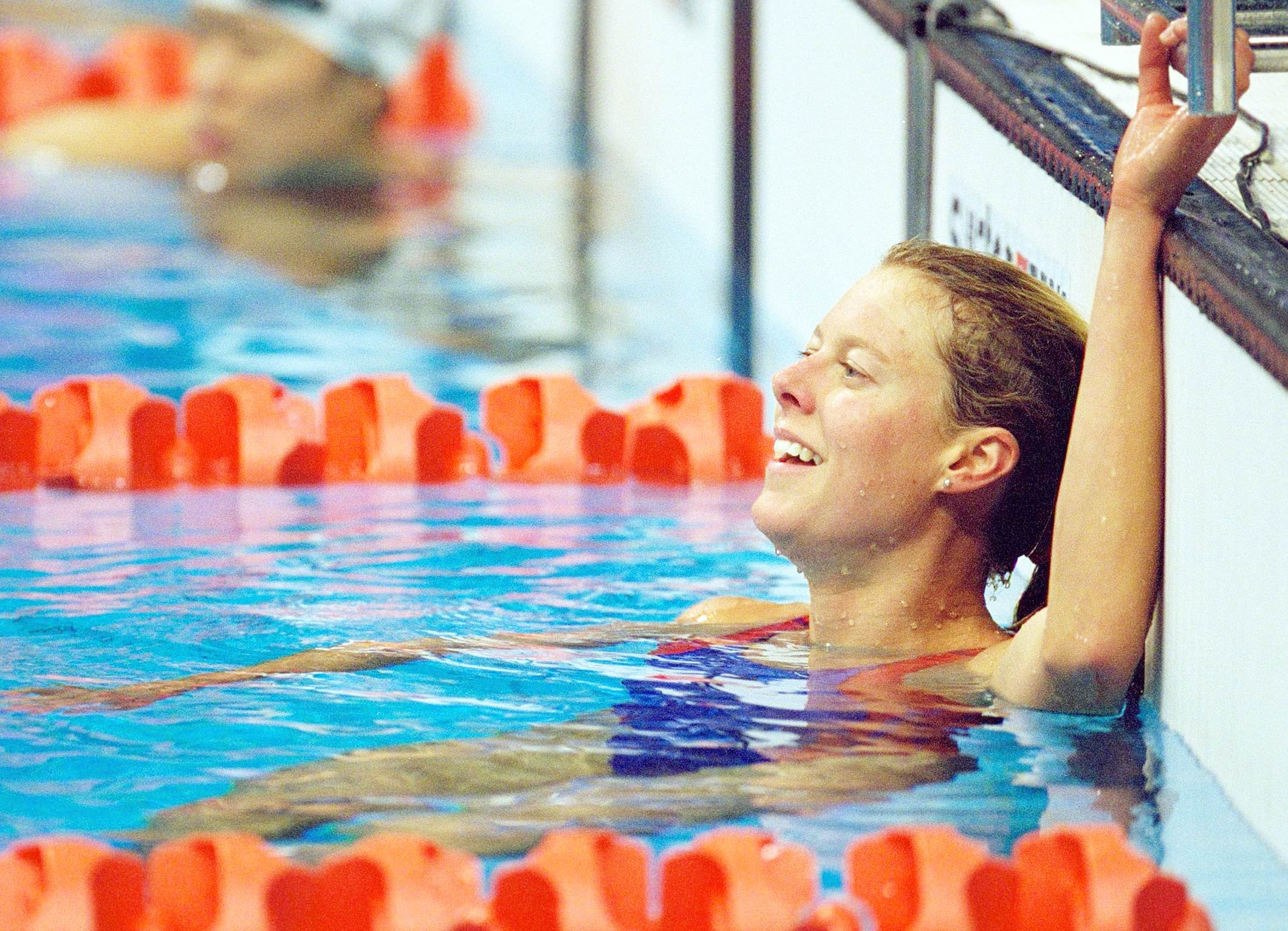

“I didn’t go clean on the ride and could have shot better, but I did enough to stay in contention. I swam a PB [personal best]. I’d always said if I was a minute behind for the run, I had a chance of getting on the podium. I found myself just 49 seconds behind.”

Cook stormed through the field to take the title. “Going into third place and knowing I had a medal was probably the most exciting point,” she said. “But as I got to the front, I thought, ‘My life is never going to be the same again’. I hadn’t gone into sport to try to become famous. But the aftermath was a bit mad.”

Once back home, she found herself bombarded by the media, and a celebrity among her medical subjects. “Patients would be leaping up and asking for my autograph,” she laughed. “Children would be refusing to go down to the operating theatre unless I signed their cast.”

Cook suddenly found herself at the crossroads again. Sport or medicine? This time, the stethoscope vanquished the épée. “I carried on until the World Championships in 2001 because they were in England,” she said. “I won those, and the European Championships, too. So I bowed out the sport as reigning Euro, world and Olympic champion. A week later I was back in the hospital. I could have gone to Athens 2004, but I realised I’d achieved more than I ever could have imagined in sport – and I’d always wanted to be a doctor. If I took more time out, it’d be hard to get back in.”

Cook became an ear, nose and throat surgeon, and eventually a general practitioner. But she has continued to closely follow her sport and its many evolutions. “The biggest change from our day is that they use laser pistols, not air pistols – and the fact they have combined the shooting and the running, which means there is even more that can change in that final event,” she said.

“It’s fun. With the shooting, it really mattered for us whether you hit a ten or a nine. For athletes now, it’s about trying to hit a target the size of an eight ring. But they’ve just been running, so they’re breathing heavily and their hands are shaky. They have to work out if how hard they run will affect their shoot.

“You’ve also had the ‘one stadium’ concept come in, where they have as many events as possible in one arena so the spectators can watch it in one place. From a media point of view, that’s better.”

Ultimately, Cook still regards it as the best all-round test for any Olympian. “That’s why Baron Pierre de Coubertin came up with the sport,” she said. “It’s still a great way to test overall skills and athletics. And it’s still really exciting.”